The scone as oasis within the travel oasis, or tea and scones, innit?

Travel is a mental oasis for me. I love the limbo of airports, the relative freedom from e-mail, the otherworldiness of exiting a subway into the unknown, the break from constant availability. Within this cocoon of travel, however, I often need a deeper oasis from the travel itself. On my recent tour of the United Kingdom and Ireland, life added the deserts of living alone, an emptied nest, a devastating divorce, and traveling on a bus with students a third my age: arid landscapes to seek oases within. So, from Edinburgh to York to Bath to Dublin, I ate my emotional way through trip challenges by consuming daily cream teas, usually alone, scone by jammy scone.

Wouldn’t cream cheese on a bagel topped by Smucker’s jam do just as well? Did I really need to fly eight time zones east for a pastry and clotted cream (the “cream” of a cream tea)? Wouldn’t scones in Utah be enough? At a Sconecutter franchise in Sandy the day before I left, I ordered honey butter white and wheat scones, thinking I would get little cakes and a side of honey butter. But no. This is the The Sconecutter procedure as I imagine it.

One, take one loaf of Wonder Bread and mash it into a lumpen, rectangular patty. Two, fry the patty in hot, not especially fresh, oil. Talk loudly with your co-workers about how much you fucking hate your boss. Three, flop the drippy patty onto a paper plate. Slice the patty in half lengthways. Four, smear a generous glob of honey butter onto each half. Five, serve this concoction to the disbelieving customer at your sticky counter. Oh, how the mighty scone had fallen. I didn’t even ask about the Scone Burger.

Origins of the scone are a bit murky, but medieval Benedictine monks and Scottish peasants share in the glory. The Devonshire Benedictines were said to reward abbey workers with small cakes, strawberry preserves, and clotted cream when jobs went well. The Benedictines then started serving tea meals to travelers and pilgrims.

The Scots, on the other hand, had always been great consumers of everything oat. The oatcake and bannock—grandparents of the scone—likely originated in Scone, Scotland, just north of the Fife peninsula and site of a medieval monastery. Perhaps the monks at Scone served small cakes just as the Benedictines did. Or perhaps the word “scone” reflects a rock-like pastry, its weight and density something like the storied Stone of Destiny (seen below and also known as the Stone of Scone), site of Scottish coronations.

This gray block looks like something you might see sitting in the rubbish heap at a construction site. You’d walk right by it. But Stone viewing is a pilgrimage for Scots since England only just returned the block to Scotland in 1996. Jacob of the Bible was supposed to have used it as a pillow, and the national red sandstone icon had formerly shared a room with the crown jewels: a crown, scepter, and sword. The dull block seems to fit the austere Scottish character better than gaudy gems.

The Scottish character and soil are also a natural fit for growing oats. This hardy cereal grass can grow in marginal soils and damp climates. Oats are also incredibly versatile. They feed horses and cattle and are also brewed into stout and the Scottish ale, caudle. The straw from oats is absorbent, low in dust when threshed, and comfortable as stable bedding. Bedding, ale, stout, feed for stock, and something to cook into porridge and bake into cakes for humans? Perfect!

Over the years, however, wealthy Englishmen wanted refined white flour, the more refined (and less Scottish) the better. White flour cakes were then combined with cream and jam, and so the scone became an aristocratic symbol. Perhaps the Scottish oatcake became a kind of culinary Neanderthal: a branch of the baked goods family tree overwhelmed by a newer, more popular cake.

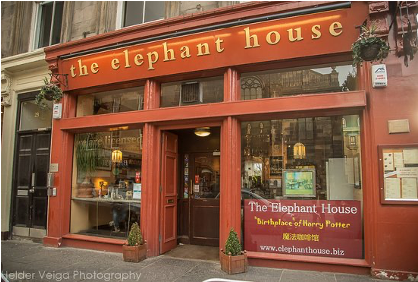

Oatcakes, cookies, biscotti, and plain and fruity scones were available to all at The Elephant House, a noisy coffee house in Edinburgh famous for nourishing and caffeinating J.K. Rowling as she penned the early Harry Potter books. (Rowling says the earliest versions of the Potter books were actually written on a train.) I sat in the back room, looking out large windows towards Edinburgh Castle. The barista traced a Scottish pine into my latte’s creamy foam. I talked art and architecture with a young Swiss student at my table as he sketched the castle, and I wrote in my journal. I went back the next day for another pine tree, castle, and pastry. (As of spring 2022, Kathy Herbert reported that the Elephant House has been closed for renovation after a fire.)

Scones as this modern quick, yeastless pastry didn’t make the culinary scene until about the 1600s, so the costumed interpreters in Stirling Castle’s Great Kitchens assured me. Grapes and currants, often added to scone batters, grow today in England’s southern counties. These fruits may have grown farther north as well since English weather was warmer during medieval times, plus the Scots were allied with France in the Middle Ages and did a lot of trading with them. Pilgrims were also streaming to many religious sites throughout England, and tourist food was bringing in the cash: a set up for today’s enormously popular “cream teas.”

So, that’s the grain and fruit part of the cream tea equation. What about the butter?

Researchers have found bog butter, also called butyrellite, in peat bogs in Ireland and Scotland. In 2013, turf cutters in Tullamore, County Offaly, came upon a stash of 100 pounds of bog butter, buried seven feet down in a carved wooden vessel (such as at right), sometimes called bog barrels. On hearing of the find, an unimpressed Irishman commented, “People down in Kerry were burying butter in the bog as recently as 50 years ago [1963].”

Bog butter is theoretically edible after centuries in the ground so great are the preservative powers of the peat. Peat bogs, an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter within a cool, low-oxygen, and high-acid environment, are Ireland’s original refrigerators. Walden Labs writer Ben Reade further comments, “If we consider ancient dairy-based economies, many people may have gone all day eating only butter quite frequently. Occasionally it would be consumed on an oatcake, or with a piece of meat or fish, but often on its own.”

Fast forward thousands of years to Dublin’s elegant Shelbourne Hotel (below). My waitress is a bit harried. Her boss had just reminded her to stock more cups and saucers at a side cupboard. She approaches.

Waitress: Are you being looked after? (Perhaps hoping she could sit down for just a few minutes, please God, while someone else served me?)

Me: Not yet. But I’d love a pot of tea and some scones. (I settle deeper into my leather chair.) I’ve been doing lots of walking! (All discretionary, of course. I’m obviously on vacation with my accent, backpack, and Dublin guidebook. Would it help if I told her I used to be a waitress?)

Waitress: Lifting an eyebrow, shifting her weight to the other foot): What kind of tea would you like? (She doesn’t seem to need a pad and pen, something I’ve always admired and never could pull off myself.)

Me: What would you suggest? (She lifts both eyebrows.) Earl Grey, then.

(Isn’t one person’s oasis always built upon the labor of someone else?)

She brings a palm-sized slab of bright yellow butter on a plate, plus three tiny jam jars. Then a silver pot of tea, a pitcher of milk, and two tall, warm scones. I ask her to take my photo. And that ancient relationship of the master and servant plays out once more on this elegant tearoom stage.

A proper scone, split in half, with jam on top of the clotted cream, was certainly not what the ancients would have eaten. A plain scone all by itself can be as tasty as a dog biscuit, and more likely what the ancient ones would have eaten. But raisins or cranberries or currants, jam, and butter or cream really make the meal. Spreading cream that’s been cooled and clotted in a shallow pan, taking small crumbly bites, spading up fallen preserves or cream dollops with crusts of scone. China plates and little ramekins or dainty pots for the jams and preserves, the sugar lumps, and the butter or clotted cream. No paper plates or cups, no Styrofoam. The pretty how and proper when as important as the what. Or the pause for the what. That pause became a lifeline as our group walked with audio guides through the Roman ruins in Bath.

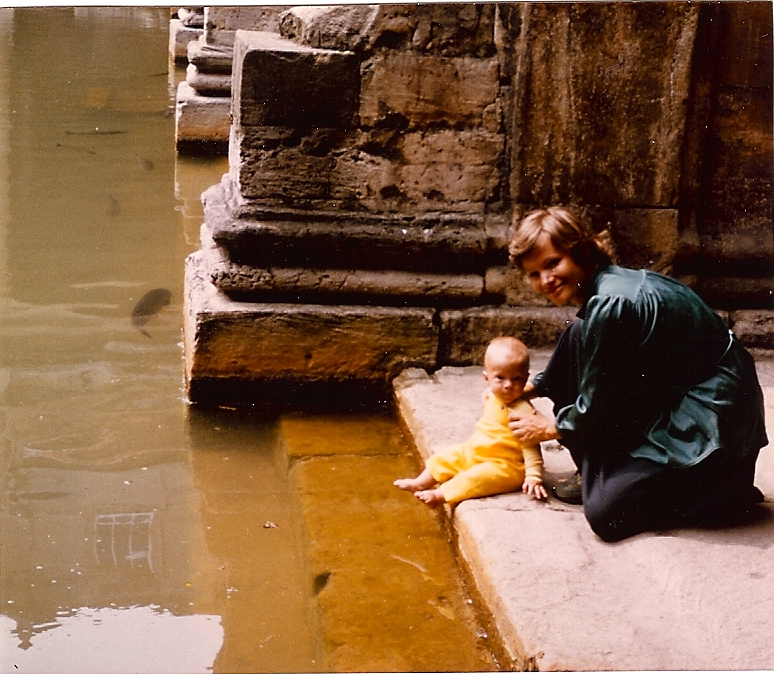

I suddenly recognized the steps and pool where I’d crouched for a photograph with my tiny son back in 1983. Married then, everything in life to my little Sam then, and so sure of my future. Then.

That little boy is now married, newly graduated from law school, and about to become a father. Sam’s father and I have divorced. Nothing is guaranteed, nothing stays the same. But that day so many years ago was beautiful, fine and filled with pride, bathed in golden rays of sunshine. Unexpectedly reminded of my recent heartache, where could I go in my melancholic fog?

Some minutes later at Costa Coffee, I sit at a counter with a pot of tea and a raisin scone. I cradle the teacup facing a busy side street. It is the stopping, the pause, that sends fortifying warmth into my bones. I sip, breathe, and let the emotional pendulum swing.

See also “Cream Tea at Bettys Tearooms”

Post a Comment